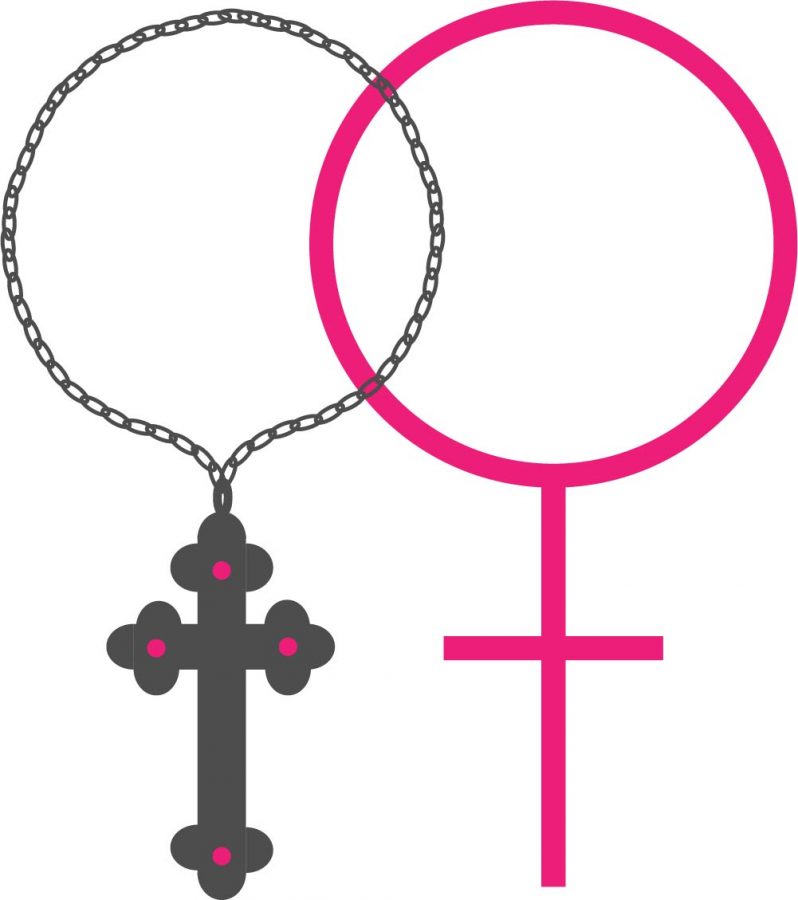

The Limits of Conditional Love in the Christian Community

October 9, 2019

“See, you have to think about it like alcoholism,” she said. “Nobody chooses to have an addictive personality, but you make the choice to continue alcoholism every time you pick up a bottle”. The ice cream I had been eating suddenly made my stomach turn as my former Young Life leader casually talked about the morality of being gay. When I came out to her, I expected the love and acceptance that Christianity promises, but was instead met with homophobia disguising itself as love.

I was 15 when I was introduced to Young Life and joined the program. It offered the stability that no other area in my life did. Once a week, I would meet with a leader over breakfast, talk about what was going on in my life and we would talk about faith for a short amount of time. My leader was a student at The University of Texas at Austin and was incredibly nice. I was never judged for what was going on in my life, the things I did or the conflicts I had. She accepted my struggles at home and with mental illness, making me feel safe in a way that my friends and family could not. Relating her life to mine, she offered an older person’s perspective on the happenings in my life.

When I went to a Young Life summer camp, the first five days were devoted to love and forgiveness. Lessons focused on these topics exclusively, as we read popular parables such as the Prodigal Son and the Bleeding Woman. Leaders shared personal testimonies of their periods of hardships full of binge-drinking, drugs, self-hatred or self-harm. We were told nothing we could do would be irredeemable in the eyes of God. No matter how far we strayed from God, or how often, we could always return. My school friends and cabinmates shared stories of the most challenging things that had happened to them and how they reacted. As stories about mental illness, death, infertility, alcoholism and abuse were discussed, we held each other, commiserating in our shared trauma. Together, we swore we would be alright, that things were going to get better and we would find our happiness eventually.

The next day was devoted to the subject of sin. Questions included defining sin, ponderings about why we sinned, and how we could repent. The subject of the previous day’s sermon suddenly was as clear as day. The previous day had encouraged us to reveal our trauma so that the next day, with our wounds still fresh, we would be filled with shame. We were not told we were sinful explicitly, but what sin was. Premarital sex, not believing in God, partying, amongst other things fell into this category of sin. Yet, debate on sin was discouraged, and we were told to accept what the speaker said as truth and “really take it to heart.” We felt guilty for the rest of camp and were told, “it’s good you feel guilty because it means you’re grappling with your demons.” One night as I left our room to make my nightly trip to the vending machine, I saw a girl sobbing on the communal couch. Her leader and one of her friends tried to console her and tell her she wasn’t going to Hell for her sins, but she was inconsolable. She had sex with her boyfriend and was convinced she couldn’t redeem herself in the eyes of their God.

I don’t believe that religious camps or groups are inherently damaging, but in my experience, Young Life as an institution has pervasive issues that need to be addressed before I would be willing to ever consider them a well-intentioned organization. The same problem that poisons Young Life is present in many Christian organizations: the subjective and ignorant concept of shame. Religious orthodoxy and the hateful sentiments that fuel it are often viewed as something that only occurs in groups such as the Westboro Baptist Church that are explicitly vocal about their hate towards marginalized communities. It’s viewed as rural billboards that announce “HOMOSEXUALS REPENT!” or parents who throw their child out onto the streets for being gay. The truth is, homophobia is present in a much more subtle way.

In my time at Young Life, I was never met with explicitly homophobic comments, yet there was always a muted air of hostility towards the idea of it. As much as I love my former leaders and believe that they genuinely care about the kids, they still believe being gay is immoral and are not shy to voice that opinion. They will not “cast the first stone,” yet they will let you know that the Bible says homosexuality is a sin. They will not judge you for your orientation, but they will refrain from asking you about relationships. They will not kick you out of Young Life for being gay, but the silent ostracization will force you to leave. In the last conversation I had with my leader, she told me she believes that God made me queer, but “God made everyone with their own personal struggle in sin,” and that I should work towards not living in sin. As an organization, Young Life claims to “be for everyone, regardless of background.” Each leader “must display a biblical lifestyle of sexuality,” therefore excluding anyone that does not fall under the restrictive category of “biblical”, including me.

Over the summer, I made the heart-wrenching decision to leave the church I now felt unwelcome in. Religion aside, knowing that some of your closet friends view the way you love as “sinful” and “deviant” will fill you with guilt, self-hatred, and religious shame. Young Life breeds an environment that lures people in with the promise of acceptance and love, and when trust is built, they passively shame you until you conform to their idea of godliness. For an organization that so frequently preaches unconditional love, they have a lot of footnotes.