The Question of Religious Faith and the War in Ukraine

December 19, 2022

On a warm and humid night this September, as we do every year, my family and I filed into an airy, brightly lit auditorium, clad in kippot (Jewish skullcaps) and clutching siddurim (Hebrew prayer books). We had come, stomachs full of apples and honey, to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, the Hebrew new year, with the vibrant Reform Jewish community of Congregation Beth Israel. As we sank into our seats and opened our ears to the cantor’s melody, it almost felt like a “normal” Rosh Hashanah.

Normality, alas, is a luxury the Jewish world rarely enjoys. Rising above the congregation, though covered with a white sheet, was the unmistakable figure of a Christian cross; behind it, a stained glass window depicted the descent of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost. Instead of celebrating the Jewish new year at our home synagogue, we packed into St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church — the synagogue was still recovering from an anti-semitic arson attack in 2021. That night, as we remembered a painful history of violence against Jews, we also contemplated a harrowing reality half a world away: the ongoing war in Ukraine. Neither the conflict nor its senseless brutality need an introduction, but one angle has, in my opinion, been too oft-overlooked. In addition to ethnic and historical hostilities, Russia’s February invasion was precipitated by a tense religious divide — one with parallels to our own struggles over faith.

Since the 16th century, Orthodox Christians in much of Eastern Europe, including Russia and the Ukraine, have fallen under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Moscow, a bishop with positional authority over other hierarchs in the region. Though Ukrainian Christians have enjoyed varying levels of independence from Moscow over the following centuries, they have consistently been considered a part of the greater Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). That status changed in 2018 when Bartholomew I, Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople (and traditional arbiter of ecclesiastical autonomy), declared the autocephaly (independence, of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine under Metropolitan Epiphanius I.

Bartholomew’s decision precipitated a deepening of pre-existing divides between Moscow and Constantinople, born out of fear of perceived Westernization. Sections of the Eastern Orthodox world were now split over the canonical status of entities previously considered to be schismatic (separated from the accepted Orthodox churches) and who could receive communion with whom. In October 2018, the final nail was hammered into the coffin of Orthodox unity when the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church officially severed ties with the Ecumenical Patriarch and barred the sharing of communion with those under his jurisdiction. The decision constituted one of the greatest schisms in Eastern Christianity since the Great Schism of 1054, which saw the Eastern Orthodox Churches split from the Catholic Church.

The 2018 schism split the Eastern Orthodox world nearly down the middle, with 110 million of Eastern Orthodoxy’s 220 million adherents belonging to the Russian Orthodox Church, according to Encyclopædia Britannica. While the severance of communion only affects members of the ROC and those churches directly subordinate to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, many smaller churches, such as the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Greek Orthodox Church under the Patriarch of Alexandria, have positioned themselves to choose sides should the schism widen. The situation is especially tense in Ukraine, where over one third of citizens before the war declared allegiance to the autocephalous Orthodox Church of Ukraine to the ROC’s 14%, according to the Razumkov Center.

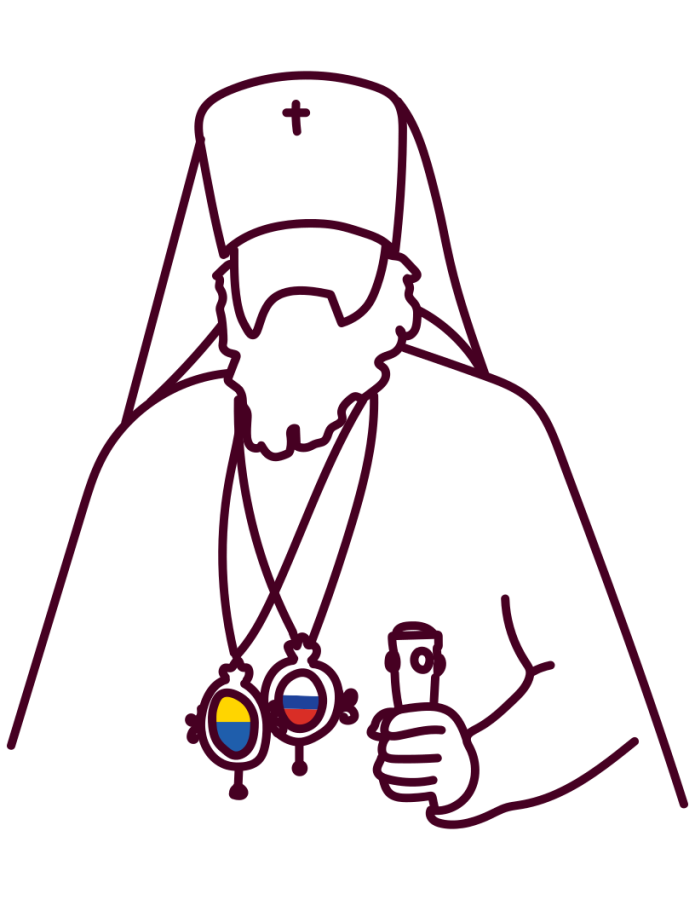

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the already brewing religious tensions boiled over, and added more gas to an out-of-control fire. The divide between the dominant churches of the two countries has been used to justify senseless violence and sow discord among communities that used to worship in harmony. Russian President Vladimir Putin described Ukraine as sharing a “spiritual space” with Russia in his justification for invasion, and Patriarch Kirill of Moscow proclaimed that Russian intervention in Ukraine was of “metaphysical significance.” In return, the Ecumenical Patriarch openly condemned the invasion, along with various other religious leaders including Pope Francis. On the ground, the schism has led to heightened animosity, including, in one especially disturbing instance, the beating of a Ukrainian priest with a cross by a priest of the Russian Orthodox Church at the funeral of a Ukrainian soldier.

A week and a half after Austin’s Jewish community celebrated Rosh Hashanah, we again filed into St. Matthew’s Church to solemnly observe Kol Nidre — the opening to Yom Kippur, the Jewish day of atonement. At one point in the slow and sober service came the chanting of Unetanneh Tokef, a traditional Hebrew Poem about, among other things, Divine judgment. The poem, in keeping with the penitent theme of the holiday, asks “Who will live and who will die… who will enjoy tranquility and who will suffer?” As we recited, we remembered the death and suffering in Russia and Ukraine and gave diffident thanks for the tranquility we enjoy and the lives we are permitted to live without fear of massacre at the hands of a hostile nation. We remembered that we, as Jews, cannot be indifferent to the religious angle of the war; in March, as if as a reminder of too familiar patterns, a Russian missile struck the site of a 1941 massacre of Jewish Ukrainians at the hands of Nazi forces.

One does not need to be an Orthodox Christian, a Jew, or otherwise religiously affiliated to recognize the horror of the war in Ukraine and to sympathize with those who, desiring only to practice their faith, have been caught up in a messy geopolitical conflict. It is a frank reality that we, as ordinary Texans, have very little power to stop the violence thousands of miles away. What we can do is open our hearts to those who look, speak, and pray differently than we do. It is easy to dismiss imperatives like these as corny and overplayed platitudes, but in Ukraine, a failure to embrace them has led to parallel spiritual and physical wars, which have resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and the spiteful separation of millions of souls. While we cannot revive the dead, mutual understanding and ecumenical engagement can help us begin to mend our spiritual wounds.