Housing: everybody needs it, and demand for it is high in Austin. In 2022, according to the Austin Chamber of Commerce, 47,442 people moved to Austin — tens of thousands more than other large cities like Toronto and Dallas. With this growing demand and a shortage of urban housing, many prospective buyers have chosen to move to Austin suburbs due to relatively more affordable prices.

Native Austinite and realtor Tammy Young said that in July, the average single-family home sold at $550,000 in Austin, but the average in the Austin Round Rock area was almost $100,000 cheaper. This statistic only measures single-family homes, which doesn’t take into account condos, apartments, and other structures which are predicted to be even cheaper in the suburbs.

“A lot of people who are moving here don’t even look in Austin,” Young said. “They look in Georgetown, Round Rock, Lakeway, [and] Dripping Springs all the time. For them, that’s Austin.”

Living in the suburbs comes with a long commute time into the city, but this commute time can still be an improvement for home buyers. For residents seeking larger homes with more space, the suburbs are still the ideal place to move, according to Young.

“To get from Lakeway to downtown Austin, it’s really only 40 minutes,” Young said. “So if you’re moving here from one of those bigger markets like LA or Atlanta, and only have a 30 minute commute downtown, for them that’s actually an improvement in quality of life. Some people really want garages and big backyards and neighborhood pools, and in downtown Austin, you can’t have all of that.”

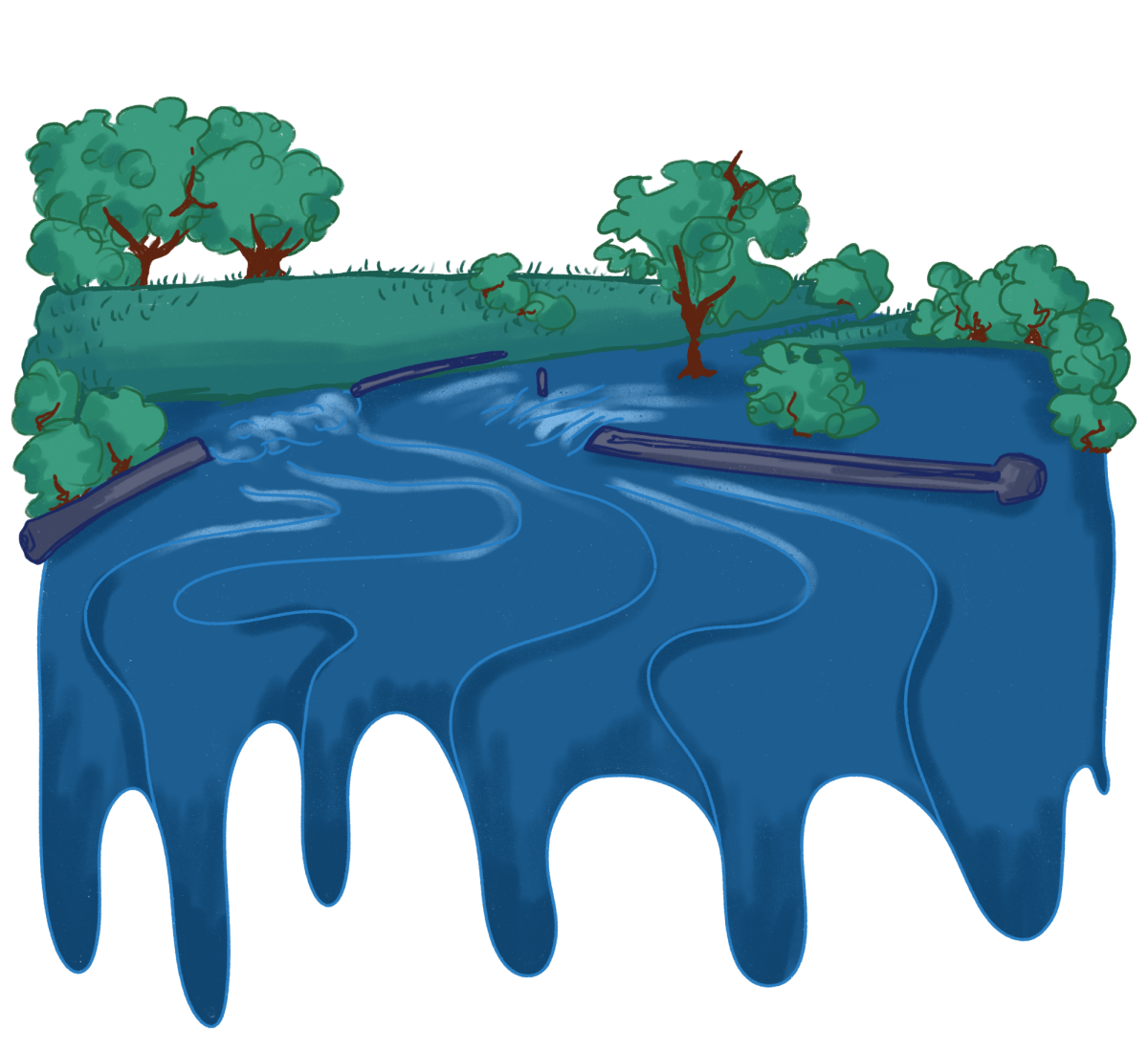

Those who choose to live in Central Austin have other concerns to think about. Freshman Megan Lorber has moved many times in her life, which has given her a full perspective on neighborhoods in Austin and the housing process.

“We’ve been able to get lucky and find houses that we like, but it’s not been easy,” Lorber said. “We’ve toured a lot of houses and they’re expensive — a lot more expensive than they should be.”

Lorber currently lives in Mueller after moving from The Grove, a planned community in downtown Austin. Two of her five moves were unplanned, due to unexpected house floods. Local policies currently don’t offer short-term housing or any programs to repair damaged houses. Young says the process of buying a house usually takes about thirty days and can involve a number of steps.

“Someone will reach out to me and we sit down and do a consultation and walk them through everything,” Young said. “If they’re getting a loan, they need to get pre-approved first. We start looking at houses and shopping then we narrow it down to ‘the house.’ We make an offer, we negotiate with the seller, and then we inspect the home, and usually there’s some repairs to negotiate. From the day you find the house to closing and getting the keys, it’s usually about a month.”

Daniel Ackerberg, the centennial economics professor at University of Texas at Austin (UT), studies housing markets and trends using statistics collected over years of data. Predicting recessions and future costs for prospective buyers is a significant aspect of realty and housing.

“More economic activity in a location because of a big University [like UT] is likely to, on average, increase demands for property and construction,” Ackerberg said. “Increased demand generally increases housing prices. One way to help decrease house prices, or at least slow down increases, would be to increase the supply of housing. That is the logic behind urban development projects like Project Connect, which will hopefully give more areas quick access to UT and downtown.”

Project Connect, according to Ackerberg, is a transit plan passed in the 2020 local election. It aims to expand transit options in the Austin area, using light rail and more services to connect people from all corners of the city. This would impact housing around UT, deflating the prices in that area, especially student housing. According to Young, some students pay $1,000/$1,200 a room per month. If large cities like Austin provide easy, inexpensive ways to commute to school or work, many areas will see less housing demand.

“What drove up our prices in Austin is demand,” Young said. “It was caused by the super low-interest rates [during COVID-19]. Everyone could afford to spend a lot more and then they would just outbid each other. If you go out to Cedar Park or Leander it’s very different. So it wasn’t necessarily inflation that drove up our prices, it was just the demand combined with accessibility.”

Austin prides itself on being a “weird city”: a difficult tagline to retain as the city’s residents become wealthier, according to Young. East Austin has been at the forefront of this change, with residents no longer being able to afford to live there, a process known as gentrification.

“It changes the fabric of the city when first-home buyers are spending $700,000,” Young said. “It’s a different community. Every time a house sells, it changes the taxes for the other houses. That’s what really makes East Austin not affordable for long-time residents. The taxes are going up so fast.”

Although Austin is currently struggling with demand, this doesn’t mean it always has to. With new affordable housing propositions and plans like Project Connect passing, concerned citizens can rally, via votes and petitions, for an increased supply of houses and lower housing costs. According to Young, Austin residents just need to keep fighting for affordable housing and telling our leaders about neighborhoods that are struggling. It’s just as much their Austin as it is yours.