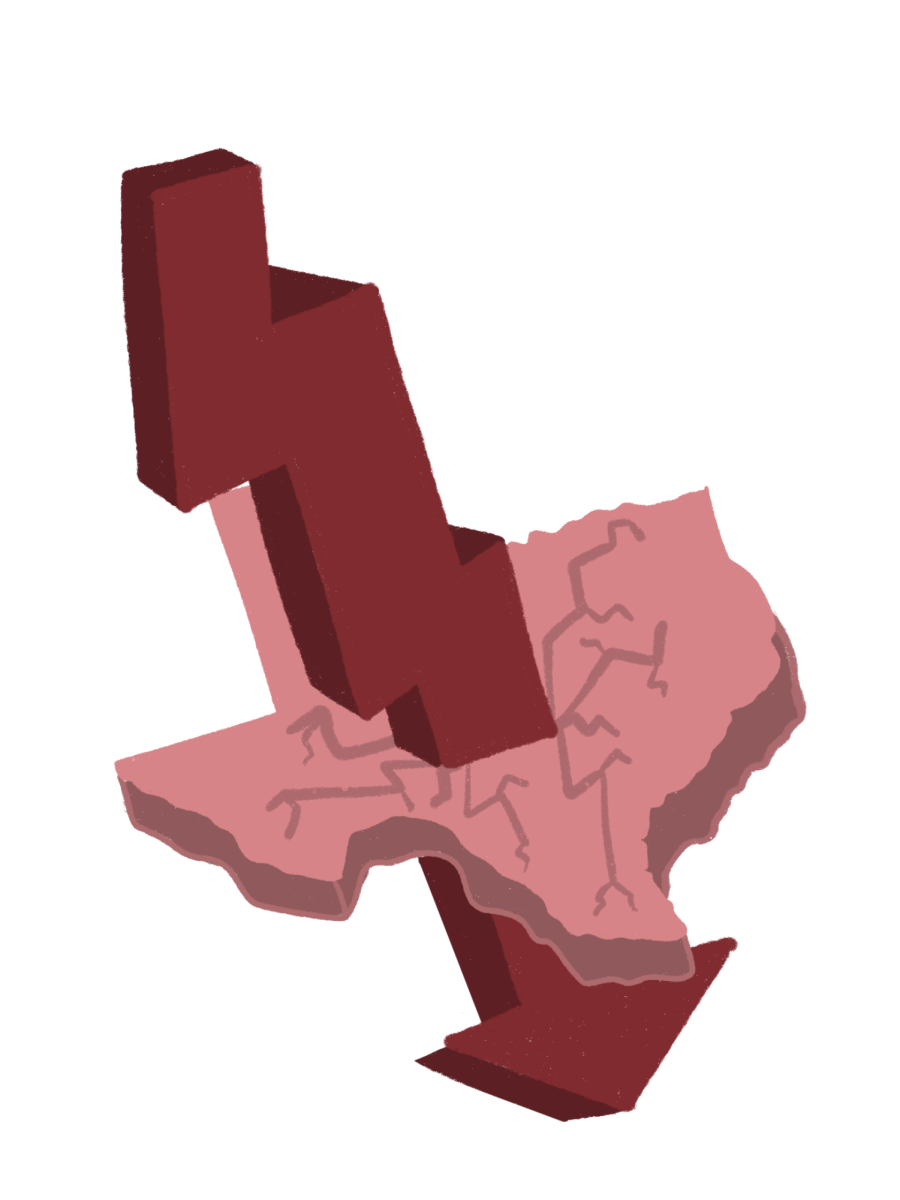

With impending budget reductions and jobs being cut, the Austin Independent School District’s (AISD) budget may turn out to be unsustainable. Moreover, with the continuation of a budgeting system that draws money from high-valued property area districts to low ones, a sign of change with the current system may not be likely.

In Texas, school districts containing high-valued property usually depend on residents and property taxes to fund their schools. The state of Texas then distributes some of the money those districts put in to fund many other school districts with lower property values, which is called the Robin Hood system. This system, established in 1993, seeks to give equitable educational opportunities for all students by restricting the amount of money that higher-valued property area school districts spend on public education and earn through property taxes.

Although this money assists many underfunded school districts, district employees such as LASA principal Stacia Crescenzi, feel that the funding is not always used best for the purpose it was allocated towards.

“The state of Texas says it distributes that [money] to these other districts,” Crescenzi said. “And yeah, we know some districts that get that money, but what goes in doesn’t equal what goes out. And so then those tax dollars that were put there for education, the governor can use for anything, road projects, salary, like anything.”

According to Ed Ramos, AISD’s Chief Financial Officer, the amount being spent on this system has changed the district’s budget over the years. With the district sending 56% of local tax collections back to the state, a 250% increase from 2016, this averages to over $900 million. This, he claims, is “enough to fund another AISD.” Although some districts need the funding distributed from the Robin Hood system, Ramos feels a change is needed in the formulas that determine the amount of money districts send. This amount is formulated by evaluating a district’s revenue from local property taxes, and if it surpasses what the state deems necessary for the school’s programs and student categories for the district to function, it goes back to the state.

“In the formulas, [they should] reduce the amount that wealthy recapture districts send back to the state,” Ramos said. “Because, right now, we’re sending too much, and [they should] just reduce the overall burden on property-rich school districts.”

In addition to not changing the formulas, the state has neglected to have a system to even review the formulas. This may result in an inadequate estimation of districts, according to Crescenzi.

“Not having a structure or a system in place to look at that algorithm every, say 10 years, doesn’t make sense,” Crescenzi said. “Round Rock doesn’t look the same as it looked in the 1990s, Austin doesn’t look the way it looked, the economy doesn’t look the same, house prices don’t look the same. To not have a system in place that is reflective on that doesn’t make sense to me.”

Although AISD and the Austin area are generally considered to be property-wealthy, more than 50% of AISD students have free and reduced lunch plans, approximately 56% are considered economically disadvantaged, and some schools even have populations where 97% of students are considered economically disadvantaged according to AISD.

While the Robin Hood system does not directly correlate with AISD’s budget reductions, a large change in the AISD budget stems from the amount of funds that they have been recapturing and returning to Texas. Budget reductions are mainly aimed at reducing budgets for vacant positions, as the payroll accounts for 87% of AISD’s budget.

“We try to prioritize and really concentrate on positions outside of campuses,” Ramos said. “So that means we look at our operational positions, central office positions, and as those become vacant, that’s where we look at reducing those positions from the budget. So we try to have as least of an impact on campuses as we can.”

Although the district aims to have the least impact on campuses when deciding where to cut spending, there are times when that falls through. Jessica Fisher, the LASA Art and Fashion Design teacher, recently had her fabric budget cut by the career and technology education department (CTE).

“What happened is [CTE] wants us to have pathways (multiple levels of one subject) now, where there are three classes back-to-back,” Fisher said. “What happens is, if you do not fall under [those classes], then they need to cut budgets from someplace.”

Budget cuts for school spending can affect both students and staff in a multitude of ways such as vacant positions and less of a budget for supplies, which is why the district tends to distance itself from this. Not only does it affect the school by reducing expenses, but it can personally affect teachers and students educationally.

“For students, it may just take longer to get the materials that we need, for me, it is paying out of my own pocket for materials,” Fisher said. “It makes our job a little harder to kind of figure out how we can best serve the students as we get you the materials you need for projects.”

In November 2022, voters passed a $2.44 billion AISD Bond, which funds the modernization of older campuses and increases pay for teachers. The bond, outlined by Adriana Cedillo, an Executive Director of Financial Budget and Planning at AISD, does not directly help with expenses at risk budget cuts.

“Having a bond gives the opportunity to lessen the burden that the General Fund has covered in the past year, like repairs or maintenance on old equipment and lesser utility costs,” Cedillo said. “But because a bond is typically a multi-year program, it takes time for these savings to come to fruition.”

According to Cedillo, to keep the AISD budget sustainable, the district will continue to analyze its funds to determine what will happen in future years. If there is no increase, the financial department will look at budget reductions and go through with it as a viable option.