How COVID-19 Highlights Disparities Across AISD

April 14, 2021

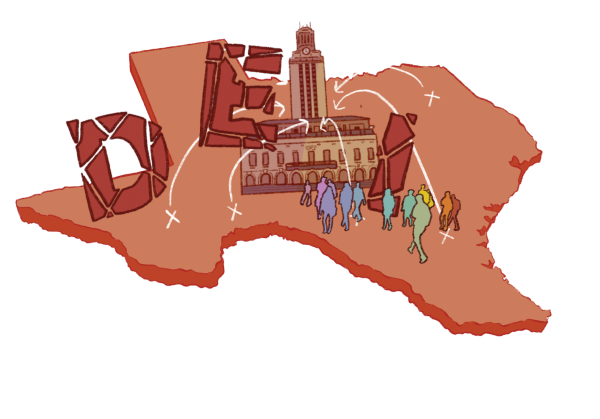

According to the University of Texas (UT) Institute of Urban Policy Research (IUPRA), more than 55% of Austin Independent School District’s (AISD) student population qualifies for free or reduced lunches, with a majority of those students attending schools with a higher Black and brown student population. Throughout Austin’s history, Interstate Highway 35 has separated the city’s poorer communities and communities of color, who reside on the eastern side of the city, from wealthier predominantly white communities, who reside on the western side, according to the Austin American-Statesman.

According to IUPRA research associate Ricardo Lowe, schools with a higher population of students of color also have a higher percentage of disciplinary issues between those students and their school. Lowe also added that within these margins, Black students comprise the largest portion of students who are penalized.

“You have to really look into what it means for school resource officers to be in the spaces where Black families and Black students and brown families or Brown students don’t necessarily have great relationships, or great trust in policing, because we saw what happened with George Floyd,” Lowe said. “This is something that is being shown to you, and you have to really start listening to people more.”

Before the COVID-19 pandemic was an issue, a large problem Black and brown communities living in East Austin were facing had to do with school closures in their area, according to Lowe. In 2019, AISD announced 12 school closures, nine of which were within Austin’s east side.

“Even before the school closures were announced, you’ll see that Black families had issues with the way that their children were being treated inside of the schools in terms of school discipline, in terms of school resource officers disproportionately disciplining their children, in terms of academic achievement, in terms of the school-to-teacher ratios, there were so many different things,” Lowe said. “Even after the pandemic, you really had those issues and they continued to persist, they’re a little bit more pervasive, in fact, because COVID-19 really has exposed some of those things a lot more.”

House District 49 Rep. Gina Hinajosa is a policy maker who has spoken out about her concerns with school segregation within Austin. Hinojosa was also a long-time board member of AISD and has two children who are AISD students.

“My office did a study about it over the interim, and what we found was that we looked at segregation two ways — we looked at it racial and socioeconomic segregation,” Hinajosa said. “In both of those categories, [Austin] ranked as one of the worst-segregated, by both measures, of large districts in the States.”

Lowe said this eventually caused a shift in these communities, overall leading to many parents un-enrolling their children from AISD. A report done by IUPRA showed that the number of Black students enrolled in AISD from ages 5-17 declined by 18% between 2000 and 2010. According to Lowe, Black families were more likely to move out of Austin completely, whereas Hispanic communities were more likely to enroll their children in local charter schools. Lowe said that in suburban communities like Hutto, the Black population has increased by 256% since 2000.

“A lot of the Black families that you’ll see that are moving out of AISD are going to the suburban areas, they’re going to Round Rock or Pflugerville or Hutto, they’re going to these different types of spaces, and suburban areas are definitely seeing a large increase in Black population,” Lowe said. “I wrote a report last year, or maybe a year or two before, about charter schools. And you’ll see that the charter school population in Austin has increased substantially while the AISD population is declining. So that tells you that even though affordability is having a detrimental effect on Hispanic communities, a lot of these parents are taking their kids out.”

Hinojosa said she first became interested in researching and fighting for a more equal learning environment between schools within Austin after hearing AISD board member Ted Gorden speak out about the wide disparities across AISD. According to Hinajosa, this is an issue that many policymakers within Texas do not notice the severity of.

“It’ll be interesting to have the State of Texas, or even the Texas Education Agency, do a review of school districts and have some kind of data that is supported by the state to say this exists,” Hinajosa said. “It’s happening, segregation, socioeconomic and racial segregation. And then a review of our funding policies, a review of our accountability policies to understand whether there’s anything that’s in them now that is incentivizing that segregation and whether there’s anything that we can do.”

AISD’s Helping the Homeless campaign is still working to help students and their families, even during a virtual school year. Rosie Coleman, a coordinator and homeless liaison for the district, said she has also seen changes in the students she works with. This year, Coleman said that there are around 870 students within the program and qualified as unhoused by the McKinney-Vento Homeless Act, with around 70% of those students being “doubled up”. Which is when students and their families cannot maintain their own household, so they are living with others in another home, according to Coleman.

“But when we talk about the students and families, we should really be saying families that are in transitional living situations,” Coleman said. “ It is so common for many people, throughout their lifetime, to be put in a situation where they have to live with family or friends for a while because they can’t afford something so people really don’t identify the label of homeless.”

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, many students and underfunded schools in segregated areas have fallen behind and are in threat, according to Hinajosa. Almost a full year later, in a mainly virtual learning environment, students are now expected to take a State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness (STAAR) test for the 2020-2021 school year, which is used to fund schools as well as determine a student’s eligibility to move on to the next grade.

“But it shouldn’t determine school funding,” Hinajosa said. “But definitely, it’s the lower-income schools that struggle most with meeting standards on the STAAR test. Just taking the test is a stressor for schools, and also schools are having to figure out how to do this in person. I mean, they’re just figuring out how to get kids back in the classroom, much less how to administer a very regimented test.”

Lowe said that AISD and districts across the nation need to be listening to the families who are speaking out. According to Lowe, this means that the district needs to also reach out to the families, not just wait for them.

“AISD has got to be more inclusive of voices who don’t always get a chance to show up to the table, if you’re holding community conversations, Black people are not always at those meetings,” Lowe said. “It’s not because they don’t always want to be at the meeting, it’s because some of them are too busy trying to get things done in other areas of life, and they don’t have time to be in these spaces. So you have to go to them. Sometimes you’ve got to go to the churches, the Black churches, sometimes you’ve got to go to the barber shops, you have to do that. But if you don’t make any effort in doing that, and understanding what this means, what does that say about equity in your district?”